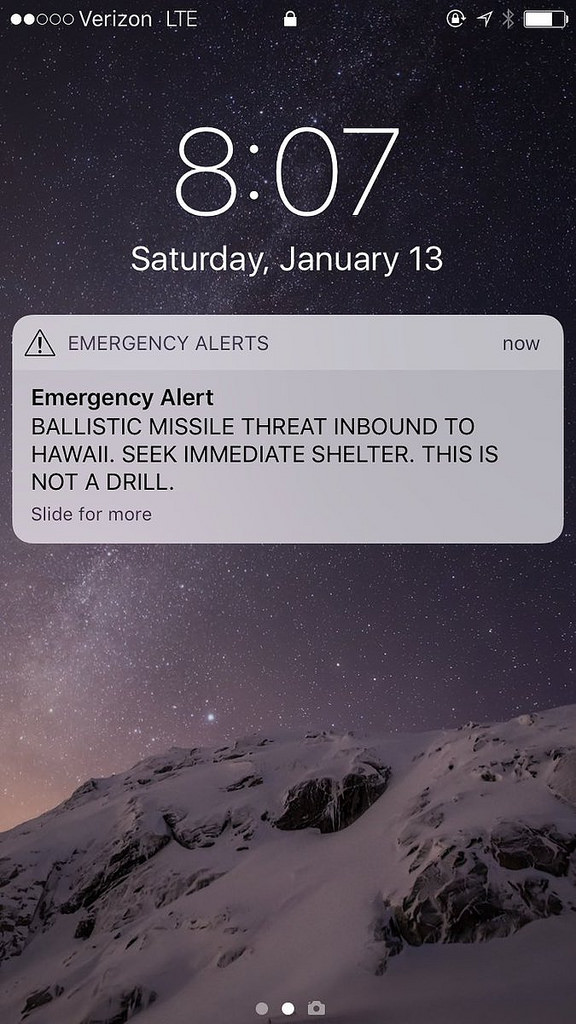

On January 13 2018, Hawaii residents and tourists were shaken by an emergency alert on their cell phones that read: “BALLISTIC MISSILE THREAT INBOUND TO HAWAII. SEEK IMMEDIATE SHELTER. THIS IS NOT A DRILL.” This message sent people across the islands scrambling to find shelter, food, and water—their lack of preparation for such a situation, and their inability to protect themselves from the threat of imminent devastation, brewed great panic. Tourist Michael Sterling remembers thinking, “What could we do? There is nothing we can do with a missile.” Hotels advised guests to remain in their rooms, and newscasts reiterated that, “If you are indoors, stay indoors. If you are outdoors, seek immediate shelter in a building. Remain indoors well away from windows. If you are driving, pull safely to the side of the road and seek shelter in a building or lay on the floor.” Thirty-eight minutes later, a new alert popped up on phones: “There is no missile threat or danger to the State of Hawaii. Repeat. False Alarm”—a state-sanctioned “never mind, just kidding.”

An error like this can lead to the dismissal and distrust of emergency alerts, but it also demonstrates the powerful role that technology plays in disaster response and underscores the importance of its refinement. While technology has the capacity to be incredibly useful in disaster response, its success is contingent upon effective and competent administration.

The erroneous alert came at a time of immense volatility in the relationship between the United States and North Korea, exacerbating the uneasiness felt by the American public with regard to their own general safety. It also followed a failed nuclear siren test in December 2017, emphasizing the state’s unpreparedness with disaster communication. While the second, clarifying message brought immeasurable relief to residents and tourists of Hawaii, it nevertheless could not erase the panic and emotional turbulence prompted by the erroneous first alert. Such an event threatens to confirm the perception of the American government as unnervingly incompetent; it also raises questions about the validity of emergency alerts and technology’s part in disaster response. How could such a catastrophic mistake possibly be made, and why did it take 38 minutes for a message of its illegitimacy to be disseminated? Officials explained the error simply, saying that an employee pushed “the wrong button.” According to The Washington Post, “The worker heard ‘this is not a drill’ at some point during a training exercise and assumed that the threat of an incoming missile was real.”

However, this justification does not change the seeds of insecurity that were nationally sowed following the event. While it is easy for the government to deflect the blame onto one individual, the mere fact that such a catastrophic mistake can be linked to a singular person highlights systemic and bureaucratic ineptitude. Furthermore, officials attempted to absolve themselves by claiming they were aware of that employee’s history of having “problems performing his job” and believing that “drills for tsunami and fire warnings were actual events;” yet, this nevertheless begs the question of why the employee was given such authority. Despite efforts to justify the mistake, government officials demonstrated the incompetence that permitted this incident.

A cancellation procedure is currently being implemented to ensure that erroneous emergency alerts can be rescinded instantaneously in the future. Beyond formal courses of action to avoid other similar occurrences, the event has also sparked discourse among the American people. Americans have felt the need to discuss how they should react in the event of a real emergency. Since then, The Washington Post compiled a list of precautionary measures one can take for protection during a nuclear attack and provided links to the various government agencies’ instructions. The BBC and Lifehacker have posted similar survival guides in response to the erroneous alert.

While an incident like this reduces the trust people have in emergency alerts, these mechanisms remain critically important in maintaining public safety; beyond exceptional nuclear alerts, they notify people of extreme weather, missing children, and imminent threats to life. Technology, generally, has gained an increasingly significant role in disaster response in recent years. Beyond emergency alerts, the Internet has provided a platform for people in need to receive aid directly; crowdfunding sites like GoFundMe and YouCaring use empathy and storytelling to raise money for individuals seeking aid. The effects of these organizations are not irrelevant; in 2014, $16.2 billion were raised globally through crowdfunding. Even the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) is using social media to communicate with victims of disasters. According to FEMA, survivors of Hurricanes Irma and Maria can receive information and ask questions on the agency’s Facebook page. Other resources include locations of Disaster Recovery Centers and Long Term Recovery Groups. The government agency “has launched an initiative to monitor social media during extreme events in the hopes of concentrating rescue efforts and potentially saving lives.”

Technology’s power to quickly disseminate information and help those in times of disaster is unparalleled, but its capabilities are still being discovered. Errors like the one made in Hawaii reveal the importance of these alerts, while also underscoring the power of technology to influence change.