Brazil has always been a country of contradictions. Perhaps no place is more indicative of this than Rio de Janeiro, a city where the most expensive real estate in Latin America shares a neighborhood with shanty towns, or favelas, as they are known in Brazil. The serenity offered by Rio’s beaches clashes with the harsh reality and carnage of urban violence. Known as a peace-loving nation, Brazil’s leading cause of death for 15-44 year olds is homicide. More people in Rio have been killed by firearms between 1979 and 2000 than all of those killed during the entire span of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict (meaning since 1948)—four times as many in fact. This astounding figure is the product of a personal war between the police and drug gangs, and between the gangs themselves, that has endured for over three decades.

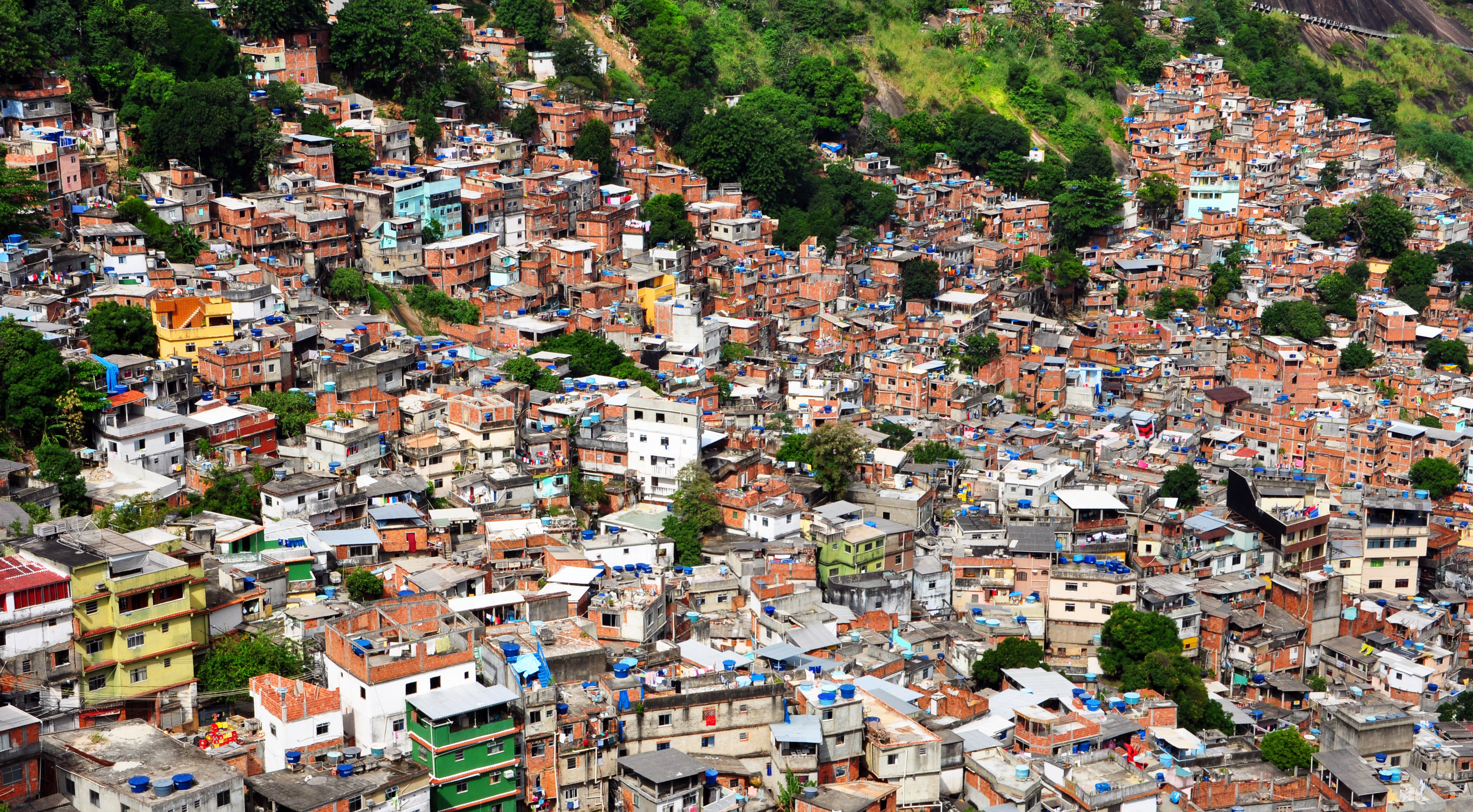

The vast majority of conflict has been limited to Rio’s 600 favelas, which sprawl over the city’s hills and are home to one third of its population. Ever since the 1980s, these informal communities have been under the control of drug gangs and characterized by a near complete absence of the state. These favelas are essentially mini failed states within the city of Rio, lacking public and private services such as basic sanitation, education, healthcare and policing. This is a reality in virtually all of Brazil’s major urban centers. It has led to the term “two Brazils,” which alludes not only to the economic inequality that has long plagued the country, but also to pronounced political inequality.

Growing up in the most fortunate of the two Brazils, I rarely get to observe the violence that has for so long been a defining characteristic of cities like Rio. People from the asfalto (asphalt), as opposed to the morro (the hills where favelas are located), essentially live in a different reality. Looking only at homicide figures for Rio, one would not be hard-pressed to think the city lives in a state of civil war. Yet, if you are from the asfalto, you are mostly oblivious to the tens of people in favelas that are killed during conflicts with the police, or between drug gangs everyday. The violence does reach the asphalt—a friend is robbed at gunpoint here, a car is stolen there—but the true carnage is limited to the morro.

Brazil is the largest democracy in South America. On paper, everyone has constitutional rights to healthcare, education, the right to a free and fair trial and freedom from abuse by the state. Yet, if you live in favela in Brazil, you are a second-class citizen. The only state presence in favela comes in the form of police repression. Speaking during what has now become an iconic interview for a 1999 documentary on urban violence in Rio, Helio Luz, then Chief of Rio’s Civil Police Force, admitted that “The institution of the police was created to be violent and corrupt, to protect the elite and keep the favela under control. How do you keep two million excluded citizens under control, earning R$112, if that? The only way is with repression.” Luz has since left the police and entered politics.

Repression is a strong word. It suggests more than just structural issues leading to economic and political inequality, but instead alludes to state coercion, a conscious effort to repress certain members of society, and an affront to people’s constitutional and human rights. It is the perfect word to describe the situation in Brazil’s poor communities. Regular policing does not occur in Brazil’s favelas. The fact that only 1.5% of homicide cases in favelas are solved is indicative of this. Police presence in favelas is associated with enmity, corruption, human rights abuses, and death. According to an Amnesty International report titled “They Come in Shooting: Policing Socially Excluded Communities”, operations occur without regard for the rule of law, disrespecting private property, human rights and employing techniques like torture and executions. The Rio Police killed 5669 people between 2003 and 2007. A study focused on 2003 showed that 1195 people were killed that year while ‘resisting arrest’, although 65 percent of the killings showed unmistakable signs of execution.

As conflict escalated over the past 30 years, the police became increasingly militaristic. The Batalhão de Operações Especiais (Special Operations Battalion, BOPE), the elite police force that does the bulk of the work when invading a favela, functions much like a special operations unit of the army. Since the 1980s, their arsenal consists of armored vehicles, M-16s, G-3s and other weapons commonly used in war situations, the use of which was virtually unheard of in urban policing before BOPE began using them. Their logo is a skull with two guns and a dagger going through it. BOPE officers have created rap songs to counter those of the drug dealers: “Men in Black, what is your mission?/Go up the favela and leave bodies on the ground/ Men in Black, what do you do?/I do things that scare Satan.” It is a police force geared towards war rather than the delivery of services.

Police abuse in poor communities is a worldwide phenomenon. The United States certainly has experience with it, with stop-and-frisk being the most recent example of one demographic being subject to stricter standards by the police. But in Brazil this phenomenon is magnified to the point where basics rights of citizenship have long been beyond the grasp of those who live in favelas. Because members of gangs are part of the community, the police tend to see all of those who live in favelas as the enemy, and treat law-abiding citizens with the same roughness that they would a gang member. Sociologist Zygmund Bauman has called this the ‘criminalization of poverty,’ where poverty is stigmatized and associated with illegal activity. It is a similar situation to what occurred during the Vietnam War, where American soldiers often failed to make the distinction between the Vietcong and civilians, resulting in daily human rights violations.

With the rise of protests in Brazil, many of those who live in the asfalto have been surprised by the level of police violence. They characterize the arbitrary use of rubber bullets and tear-gas as affronts to their democratic rights. What they do not realize is how mild these techniques are in comparison to those used in the morro. A recent political protest in the Mare favela left at least nine people dead—five alleged gang members, one police officer and an undisclosed number of innocent bystanders. Police presence was beefed up after the death of the officer, with one community leader saying “They [the police] are pointing their assault rifles at everyone. They’ve killed nine people already and are acting without any planning or control.” The non-lethal methods used in downtown and South Rio receive front-page coverage, while the incident at Mare was barely mentioned by the media.

All of this begs the question—is Brazil truly a democracy? It has universal suffrage, a free press and three branches of power, but it undoubtedly lacks equality in political and economic rights. I first began truly realizing this one evening, while I was waiting in a crowd to enter a soccer stadium in North Rio. An Afro-Brazilian boy of about 15 attempted to pickpocket someone’s wallet. Police officers nearby were alerted and dragged the boy away from the crowd, bruising his entire back in the process, his head hitting against the asphalt. My first thought was that if that had been me, a white boy from South Rio, the police would have treated me very differently. Political scientists often discuss democracy as a spectrum rather than a binary. Incidents like the one described above lead me to think that Brazil fits closer to the non-democratic end of the spectrum rather than the democratic one.