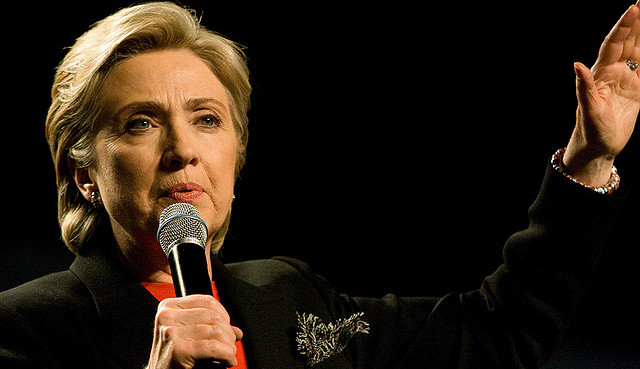

In Pennsylvania, during the spring of 2008, Hillary Clinton’s campaign faced a notable problem: white women. While Clinton courted the demographic as a key component for what could be a critical primary victory, they just weren’t biting. Barack Obama was everywhere in the media, and though projections had put her safely ahead of the Senator, polls showed white female support for Clinton falling by six percentage points in just one week. Faced with what seemed like an un-winnable media war, the Clinton campaign strategized to combat the image of Clinton as cold by emphasizing her personal — and feminine — touch, sending Hillary supporters directly into homes to engage with women and their concerns. These living room chats, her strategists reasoned, would bring Clinton closer to voters, removing a sometimes-hostile media barrier between her and the supporters she dearly needed.

Clinton ended up winning Pennsylvania by almost double digits, though the victory wasn’t enough to carry her to the nomination. The gender barriers and media conflicts at play in the state plagued the rest of her campaign as she sought to become the first viable female presidential candidate. And these struggles aren’t unique to Clinton — they illustrate the ways that female politicians must deal with their identities as women, both by dodging the insidious sexism of their field and playing up their gender as they attempt to identify with and leverage their own demographic. As the campaign tales of Democratic women in the upcoming midterms demonstrate, today’s playing field has not leveled out from the bumpy road that Clinton faced.

Among women seeking election in November is Texas State Senator Wendy Davis, who shot to national fame last June after her eleven-hour filibuster to block a restrictive abortion bill in the Texas State Senate. The move, lauded as a bold statement for reproductive rights in a state not exactly known for its forward-thinking policies, delayed the vote until after midnight, which voided the bill due to an oncoming recess. Though Governor Rick Perry successfully circumvented her feat by calling a special session to pass the bill, Davis’ filibuster was still star-making, launching immediate speculation on a possible run for governor and generating support from Democratic groups like EMILY’s List and Battleground Texas. Davis made good on the talk by launching a campaign against Texas’s outgoing Attorney General and the Republican nominee for governor, Greg Abbott.

Davis may have come out of left field with her sudden, meteoric rise, but her tactics didn’t. In 2011, she filibustered a bill cutting $4 billion from public education, drawing statewide attention in just her first term. She’s long been a supporter of women’s rights, from her stances on abortion and the pay gap to her support for women’s health services and family planning. Since the beginning of her political career on the state level, she’s been on the shortlist of legislators to watch, and she now has the kind of attention and support any candidate would envy. But it will take more than that to win Texas. Despite talk about the solid red state’s latent potential to turn blue — due to a rapidly rising immigrant population and the liberal oases of its major cities — analysts show that Texas won’t be voting Democrat quite as early as her campaign would hope. Equally pressing is the funding gap between her and Abbott: a reported $24 million, from his $36 million to her $12 million.

The personal has certainly come out with Nevada politician Lucy Flores — but she’s been the one to bring it up. Born into a family of thirteen, Flores had a troubled upbringing, dropping out of high school and falling in with a gang. After getting a GED and pursuing a law degree, she founded a legal clinic and gained a seat in the Nevada State Assembly. Now Flores is in a tight race for lieutenant governor of Nevada, a position that could easily lead to the governorship itself, especially given current Governor Brian Sandoval’s potential plans to run for Senator Harry Reid’s seat in 2016. As MSNBC’s recent profile of Flores reveals, she’s used her background as both a frame for her work as a state representative and as the backbone of her campaign. For example, she introduced a bill allowing domestic abuse victims to break their leases, citing her own flight from a stalking ex. Many of the policies Flores backs — like better sex education, increased school funding and aptitude tests for high school students — derive from her own experiences overcoming barriers to her ultimate success.

The personal story that’s drawn the most attention, however, has been the unapologetic admission that she underwent an abortion. After watching all six of her sisters get pregnant in their teens, Flores saw firsthand the outcomes of their situations. So, when she became pregnant at 16, she chose an abortion instead. As she told Huffington Post, “It was a difficult, difficult decision, but it was the right one.”

The admission came with two floods: one of national acclaim from Democrats, and one of death threats from the other side. Flores is not the first politician to disclose a past abortion: In 2011, fellow California Democrat Jackie Speier took the House floor to describe her medically necessary abortion. Flores’ confession has the potential to draw more ire from pro-lifers — her life wasn’t in danger, a cause for which even the staunchest abortion opponents can often find sympathy. Like many would-be mothers, Flores simply wasn’t ready for a child.

If Flores is notable for her pro-abortion rhetoric, one of the most visible female candidates on the national stage is notable for steering clear of the subject. It’s the moderate views of Kentuckian Alison Lundergan Grimes, a candidate for Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell’s Kentucky Senate seat, that have helped many see her as a viable challenger, even in a bright-red state. Her successful stint as Kentucky’s Secretary of State raised speculation about Lundergan Grimes facing off against the six-term senator. Her career politician father has helped supply both local support and national connections, and her rise has been accompanied by money and attention from important Democrats across the board. Her supporter list is star-studded, including names like Senator Elizabeth Warren, Steven Spielberg, former President Bill Clinton and Harvey Weinstein.

Her policies may be less liberal than her counterparts — Davis’ voting record places her as the second most liberal Texas state senator, while Lundergan Grimes shares views with McConnell on coal, gun rights and carbon emissions — but a crucial similarity is that she’s tackled gender head-on. Coming out of the primaries, she declared her intention to “break through the ceiling” to become Kentucky’s first female senator and has bashed McConnell’s record of voting against bills like the Lilly Ledbetter Fair Pay Act. But her own struggles with gender adversity have shown throughout the campaign in instances like GOP strategist Brad Dayspring referring to her as “an empty dress.”

But Lundergan Grimes recognizes the potential power of female voters, who may be able to propel a victory for her in the fall. Female voters make up a majority of the Kentucky electorate, and her plan so far has incorporated an aggressive embrace of women’s issues (except on abortion) and open acknowledgments of her gender and the role it plays in her political career. She rallied against the “empty dress” comment and emphasized her heels in both her wardrobe and her speeches. As the Washington Post chronicled, these attempts sometimes resemble those of former Alaska Governor Sarah Palin in 2008: She’s posed for pictures “wearing a tank top and jeans and wielding a rifle,” while firing rhetorical shots at McConnell. However, Lundergan Grimes has a distinct advantage over the former vice presidential candidate: She can balance Palin’s fierce hockey mom persona with appropriate experience for the position, dodging the perception Palin faced that she was tacked on to McCain’s candidacy solely to appeal to women.

By placing emphasis on their personal stories, tackling hot-button women’s rights issues and playing up gender as a tool in the campaign arsenal, these candidates have preemptively tied their candidacies to their identities as women. The move is a smart one. It’s a relatively accepted political truth that women will be subject to a higher barrier of scrutiny about their backgrounds, but these women have instead taken control of their own backgrounds and identities — and they intend to use that to their advantage.The goal is to leverage female voters, a large and significant demographic that has received insufficient focus from many politicians. But the path won’t be easy for Davis, Flores and Lundergan Grimes: Women are a difficult group to mobilize and don’t often vote their gender. But with cunning campaigns and enough luck, the 2014 midterms may offer a hint as to how successful Democratic women can be at winning over the fairer sex — information which the Blue women of 2016 may especially value.

Clinton may already be considering these female candidates’ strategies as she weighs her own plans for 2016. Women’s rights were central in her stint as Secretary of State, and she’s continued to emphasize women as she moves towards a potential presidential candidacy: Her current book tour has focused heavily on women’s issues; she sat for an interview with Glamour magazine; and she launched No Ceilings, a project that provides a global survey on the state of women. And although she refused to answer questions about a presidential run in a recent Q&A session at Facebook’s headquarters, she proudly stood on stage with Sheryl Sandberg — the company’s chief operations officer and a major face of modern feminism — to give advice on being a woman in the public sphere. If her recent activities are any hint, Clinton’s gender and her ability to leverage it, will be central to her strategy for breaking the glass ceiling to the Oval Office. And if she gets there, the question then will be whether or not the playing field for other women will finally change.

Art by Olivia Watson