On June 17, the California Labor Commission ruled that Uber driver Barbara Ann Berwick was an “employee” of Uber. For most users of the ubiquitous ride-sharing app, this ruling will sound redundant. They will see it as a statement of fact, not a decision that culminated a bitter legal battle centered upon the meaning of that ostensibly simple term: employee. And few will believe that the case – which required Uber, a company currently valued at $50 billion dollars, to reimburse Berwick for $4,152.20 in working expenses – has the potential to undo the company’s entire business model. It is easy to underestimate the importance of the California Labor Commission case, but what it lacks in monetary weight it more than makes up for in its potential to set a far-reaching precedent.

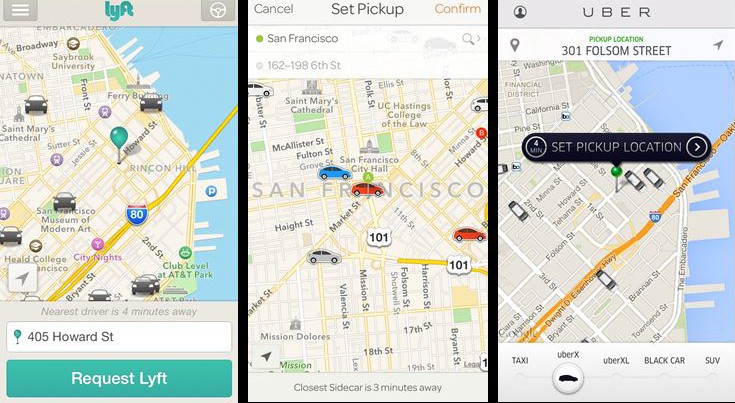

Uber’s current business model skirts around the official definition of an “employer.” They consequently avoid the regulations that come with that title. Uber contends that its drivers are “independent contractors”— self-employed individuals hired for specific services — and not employees. Like others in the “sharing economy” or “gig economy” (e.g. Lyft, PostMates, Instacart, Airbnb), Uber sees itself as a mere intermediary, connecting service providers and users, in this case drivers and riders.

The company makes significant claims to to support this argument. Drivers own their cars, are responsible for their own working hours, and are free to provide work for other contractors, such as taxi or limousine services. The criteria change if you’re looking at the IRS or state requirements, such as California’s, but generally these are all essential features of an independent contractor relationship.

But Uber’s critics insist this is a limited perspective. The primary legal distinction between an independent contractor and employee is one of control, whether control is only the result of a job or the means and methods: when you work, how you work, where you work. Opponents of Uber note that the company sets rates for its drivers, strictly monitors their performance, and gives detailed requirements such as what kind of car they drive, what route they must take, and how clean their car should be. This is arguably a form of control on how a job is done, not only if a job is done. Additionally, Uber has the right to discharge any driver. Legally, though, independent contractors may not be fired before a job is completed unless they violate their contract.

Critics also point out that the independent contractor classification is substantively beneficial to Uber. Ultimately, the difference between an independent contractor and an employee is more than just semantics. It is a difference of benefits, including health insurance, disability, and retirement. It is a difference of eligibility for employee protections, such as minimum wage, overtime, and unemployment. And it is a difference of payroll taxes; independent contractors are responsible for their entire contribution to payroll taxes.

These combined expenses increase payroll costs between 20 and 30 percent, according to a Bloomberg Businesweek Magazine article. The article also highlights a growing trend in which companies misclassify their employees’ statuses to avoid said expenses. The National Employment Law Project recently released a report accusing the sharing economy of perpetrating this form of financially expedient misclassification. If Uber is misclassifying its workers for economic reasons, it would hardly be the first. A 2005 report out of Cornell University identified that 9.2 percent of workers were misclassified as independent contractors in the state of New York.

This misclassification isn’t merely one for the courts; it affects the lives of hundreds of thousands of employees in the sharing economy. Take the case of Takele Gobena, a 26 year-old Uber driver from Seattle. He quit his job and purchased a new car for a lucrative new gig in the gig-economy. Gobena is now behind on his car payments, has no health insurance, and after expenses and taxes makes $2.64 an hour, well below minimum wage. Uber markets itself to prospective drivers by claiming that on average they will make $19.04 per hour. When drivers sign up, however, many do not understand the extra tax burden they take on as independent contractors which makes the relatively generous hourly wage far less so. They often also buy new cars to meet Uber’s vehicle requirements, as Gobena did. These are purchased in many cases through Uber’s low-credit financing program, which provides new drivers with reportedly subprime auto-loans.

Gobena’s story is admittedly not universal. Only 35.5 percent of Uber drivers consider themselves employees, according to a June 15th poll. However, that 35.5 percent is enough to challenge Uber’s current classification. While Barbara Ann Berwick is just one Uber driver among many, the June ruling that she is, in fact, an employee bolsters a class action lawsuit of 160,000 drivers similarly challenging their classification as independent contractors. The plaintiffs are seeking a ruling that will replicate Berwick’s case.

It is unlikely that the class action case will cripple Uber. A recent report approximated the cost of benefits for an Uber driver to average $5,500 per year per driver, sans mileage reimbursements. While this is a hefty fee for the company, Uber is highly successful and could likely handle the cost adjustment. The real issue at stake in the class-action case is Uber’s position as the figurehead of the burgeoning sharing economy. If the independent contractor classification stands in the Uber class action case, it could set a precedent for the sharing economy as a whole. As Uber grows in success, its counterparts in retail, hospitality, transportation, and communication will follow in its wake. A growing percentage of the labor force will be categorized as independent contractors with the dearth of benefits that accompany that label.

The plight of the Uber driver is not pressing, as there are far more egregious violations of worker’s rights, but it is an issue woefully underestimated by many in the labor movement. The sharing economy is a small but increasingly significant portion of the overall economy, and its workers are facing the potential loss of employee protections and benefits entirely.

Photo: CA Dept. of Insurance